As Duke University President from 1970 to 1985, former North Carolina Governor Terry Sanford led Duke's rise to national prominence, set in motion signature programs, and voiced aspirations that still shape the institution today.

During the centennial year of Sanford’s birth, 2017-2018, the Sanford School of Public Policy has celebrated his legacy by creating, collecting, and sharing stories of principled leadership from the Sanford and Duke community.

We also will share details of Terry Sanford’s contributions to North Carolina, Duke, and the nation via a second social media campaign centered on a series of short films about his life.

From March 13- July 28, 2018, we invite students, visiting alumni, parents, and friends to a historical exhibit based on Duke Archives which is on display in the Mary Duke Biddle Room at Duke’s Rubenstein Library, titled "Terry Sanford -- A Change Leader for Duke." As Duke's President from 1970-1985, Sanford led the institution’s rise to national prominence, set in motion signature programs, and voiced aspirations that still inspire Duke today. Through historical photographs, Sanford’s speeches and diaries, and the words of his contemporaries, the exhibit explores race relations and equality, student leadership, the arts, public service, and politics during the defining era of “Uncle Terry” Sanford.

Finally, through co-branding, we will tie ongoing activities of the school - such as our distinguished lecture series, activities of POLIS (The Center for Political Leadership, Innovation, and Service), and others - to the Centennial.

Look for #TerrySanford100 on the Sanford School of Public Policy’s social media accounts.

Please contact Karen Kemp or Mary Lindsley if you have additional ideas for celebrating the legacy of "Uncle Terry."

Principled Leaders

Alma Blount, director of Sanford’s Hart Leadership Program, has dedicated her life to understanding the transformative power of leadership.

With a background in political organizing, Blount spent the early 1980s working in Central America during the anti-war movement. “I became interested in learning how to go into a community, to listen deeply to the stories of the people who lived there, and to build a network of relationships.”

However, after security forces murdered six Jesuit priests she knew well, along with their housekeeper and her daughter, Blount faced a turning point. She opted to take a break from activism and began to pursue her Master of Divinity degree at Harvard after obtaining a scholarship to attend.

While at Harvard, Blount took an “adaptive leadership” class with Ronald Heifetz at the Kennedy School, a decision she credits as one of her best. A curriculum based on understanding lived experiences, the adaptive leadership framework gave Blount the tools to reexamine her professional life. It also provided her with a sense of healing.

Before encountering adaptive leadership, Blount said, “I thought that if you were at the helm of an organization, if you had some courage, if you said yes and no clearly, if you held things together, you were a leader. I did not see that leadership was a skillset you could get better and better at over time, and how enormously practical the adaptive leadership framework could be in terms of work in the world.”

Although she had planned to return to activism, an old friend informed her about Duke’s Hart Leadership Program, America’s first endowed leadership initiative for undergraduates. The program allows students to engage in service work and pursue socially innovative ideas while growing their leadership capabilities. Blount joined the Sanford School in 1994, and succeeded Robert Korstad as director of Hart in 2001.

Under her leadership the program has become nationally renowned for its unique combination of academics, experiential learning, and critical self-reflection.

While her colleagues at the Kennedy School initially were skeptical of her desire to teach adaptive leadership to undergraduates, Blount believed they would be excited to take on the challenges of complex problems. Blount was right, and participants consistently rate the program among their best experiences at Duke.

Blount, the recipient of the 2014 Susan Tifft Sanford Undergraduate Teaching and Mentoring Award, has left an impression on hundreds of graduates. Gino Nuzzolillo BA’20 says, “Alma taught me what it means to be vulnerable, creative, and tireless in the art of exercising leadership. Few people have changed how I perceive the world and behave in it like Alma.”

Sunny Frothingham PPS’14 demonstrates principled leadership through her activism in service of marginalized groups. As a senior researcher at Democracy North Carolina, she uses both research and advocacy to expand electoral participation and address issues of social justice.

Prior to joining Democracy NC, Frothingham was a senior researcher for Women’s Economic Policy at the Center for American Progress in Washington, D.C. and an organizer for Everytown for Gun Safety.

A public policy and women’s studies student at Duke, Frothingham was also a campus activist, working to promote policy reforms on some of the same issues she now deals with at Democracy NC. As co-president of Duke Students for Gender Neutrality she advocated for trans-inclusive student housing and health coverage. Frothingham also served as the Duke Student Government Director of LGBTQ Affairs and Policy and worked closely with university administrators to facilitate policy changes.

She graduated with high distinction for her honors thesis, which tackled contemporary approaches towards gender-neutral housing in higher education. She also received the 2014 Dora Anne Little Service Award in recognition of advocacy work that extended beyond the classroom.

Classmate Jacob Tobia T’14 said: “Sunny’s support of the trans community and tireless advocacy for gender-neutral housing during her time on campus played a substantial role in making Duke the place it is today.

“Her commitment to Durham, to North Carolina, to social justice, and to democracy are unwavering. In a world where political organizing is often dry and lacking in joy, she brings an effervescence, wit, and brilliant sense of humor that invigorate everyone who is fortunate enough to work with her. A veritable force, Sunny’s positive impact on the state of North Carolina will blossom for years to come.”

“Professor Kristin Goss exemplifies the ethos of the Sanford School of Public Policy and demonstrates principled leadership both in her scholarship and her teaching. She engages in rigorous policy research, serves as a vocal advocate for issues at the core of our national policy debates, and exhibits genuine compassion toward her students.

I wrote about Professor Goss in my application to Duke’s MPP program because I saw her presence and work as a tremendous benefit of attending Sanford. I admired Professor Goss’s dedication to gun control and to women’s representation in all facets of political and civic life and how she chooses to face the controversies head-on in op-eds, on podcasts, and within academia. Later, as a second-year student, I had the honor of working under Professor Goss as she advised my master's thesis with the D.C. Office of Human Rights. She pushed me to ask more nuanced questions of my client, of the existing research, and of myself.

I had the privilege of working with many wonderful professors at Sanford, and I will never forget how Professor Goss supported me as a student and a person. When I emailed Professor Goss expressing that I was dealing with some trying personal issues, she immediately (within 5 minutes) asked to Skype. We talked through what was going on and how I could best finish the program strong.

This experience informs how I approach relationships with my co-workers. I remain extremely grateful for the example Professor Goss has created for Sanford students and especially for other women working in the policy world.”

-- Leah Elliott MPP'16

The second African American woman in the United States to become a board-certified pediatric cardiologist, Dr. Brenda Armstrong B.S.’70 and is not only an expert in her field but a champion of diversity.

Now dean of admissions for Duke School of Medicine, Armstrong had as a child shadowed her physician father as he made house calls to African Americans in the community. This, coupled with a Saturday job at her uncle’s pharmacy, kick-started her ambition to enter the world of medicine.

As part of Duke’s third class of African American undergraduates, Armstrong majored in zoology before attending medical school at Washington University in St. Louis, where she was the only African-American woman for three of her four years. During Armstrong’s undergraduate years she experienced prejudice and racism, leading her to become an on-campus activist. She risked expulsion and more when she participated in the 1969 Allen Building protest, believing that Duke needed to hear and address problems of race at the university.

Her courage was inspired by her family’s involvement in the civil rights movement. As her father fought for the right to vote, he met with Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., giving Armstrong the opportunity to hear the charismatic leader speak in her hometown of Rocky Mount, N.C. This event motivated her to fight against those who would seek to restrict the rights of minorities and lead the way for African American women in science.

As the recipient of the Duke University Distinguished Faculty Award, a Golden Apple Teaching Award, and the S.L Katz Pediatrics Outstanding Faculty Teaching Award, Armstrong is a widely recognized surgeon and teacher. Under her leadership as dean of admissions, the Duke Medical School achieved record numbers of graduating females and minority students.

On her desire to help others, Armstrong told Durham Magazine: “My life, and whatever roles I’ve been fortunate enough to find, has been about giving back. I have wonderful gifts that no dollar amount could bring.”

A renowned education attorney Ann Majestic BA’70/JD’82 left a lasting impact on all those she met.

As an undergraduate, Majestic served as vice president for what is now Duke Student Government and forged a connection with Terry Sanford, then president of Duke. As a mentor to Majestic, Sanford wrote her a recommendation letter for Duke Law School, where her passion for public education flourished.

At Raleigh-based law firm Tharrington Smith, Majestic’s work centered on improving public education throughout North Carolina and she quickly emerged as one of the most passionate and determined attorneys in the field. During a two-week-long hearing related to contentious budget management issues, colleague Ken Soo recalls telling Majestic that he did not think he would succeed in his direct examination of the accountant in question. Her response was simply, “You have to.” This resolve is evident throughout her career as she tirelessly worked toward ensuring every child has access to a proper education.

Perhaps the most important moment in her career came in the case of Leandro vs. North Carolina. In a 1994 lawsuit filed by five low-wealth counties in the state, the plaintiffs argued that poorer school districts could not provide adequate education when they had such limited tax revenues.

In a landmark ruling, the N.C. Supreme Court said the state, not local school districts with varying resources, bears the responsibility to ensure a “sound basic education” to all children. As the lead attorney for Tharrington Smith’s education sector, Majestic was a prominent figure in these disputes.

She also played a key role as the Wake County school board attorney, where she encouraged the use of family income rather than race to guide student enrollment. Jack Nance called her “the most competent advocate for children and educators this state has and most likely will ever know.”

Majestic was guided by a drive to do the right thing, says close friend Meredith Scrivner BSN’72. Scrivner remembers when faced with tough issues or policy matters, Majestic would say: “Do what is right for the child and you will end up in the right place. It’s not that hard.”

It was not just those close to her who were touched by Majestic’s influence. In a letter to her daughter Catherine, a former UNC Chapel Hill student detailed her experiences in an educational inequality class where Majestic was a guest speaker. The student spoke of feeling awe at the work of Majestic in Wake County, realizing that she too wanted to become a lawyer. She also said, “Her thoughtfulness and passion that day in 2004 struck a chord with me and sent me on a different career path than I had imagined for myself.”

Albert Kirby, attorney, said she had a way of making “unimportant” people feel “very important.”

Majestic was honored for her service to education law with the 1998 Distinguished Service Award from the North Carolina Bar Association and a Lifetime Achievement Award from the National School Boards Association Council of School Attorneys. She died in 2014 from breast cancer.

With the fifth-lowest adult obesity rate in the nation, California is often presented as one of the healthiest places to live. Yet, as Duke alums Claude Tellis BA’95 and Kareem Cook BA’95 MBA’00 found out, the reality of life for low-income and minority communities is starkly different.

Aiming to educate people in the African American community about healthy lifestyle choices, east coast natives Tellis and Cook made the move to Los Angeles in 2002. Upon arrival, the pair were shocked by the prevalence of child obesity, affecting 15 percent of all children in California. Thus, their campaign for healthier schools began. Despite opposition from Coca-Cola, the pair won a contract to install the first healthy vending machines across the LA school district.

Driven by a desire to prevent common diet-related illnesses in the African American community, the duo set out to expand their platform. This led to the purchase of Naturade in 2012 and their launch of VeganSmart, a low-calorie, high-nutrient meal replacement product, under the Naturade brand.

Priding themselves on being “the only plant-based company of our size to focus on underserved communities,” Tellis and Cook want to change the perception that making healthier choices means spending more by providing full meal replacement products for as little as $3.

Recognizing that low-income and African American communities often suffer from lack of access to healthy choices, Tellis and Cook also have made their products widely available, in stores such as CVS, The Vitamin Shoppe and Shop Rite.

Their entrepreneurial road hasn’t been completely smooth. “During our journey, I’ve lived in the office for a year, I’ve been without a car, we’ve struggled for long periods,” Cook said in an interview with BE Modern Man.

Tellis says, “We have been able to break through because people know that it hasn’t been all about making money for us. We have turned down jobs at major companies to pursue a dream of owning a company making a real impact in our community.”

Fighting human trafficking was not what Susan Coppedge PPS’88 expected to be doing after leaving Duke. But an experience while she was an assistant U.S. attorney put the Stanford Law grad on the path that eventually would lead to her current job: Ambassador-at-Large to Monitor and Combat Trafficking in Persons and Senior Advisor to the Secretary of State.

A fellow federal prosecutor was bringing one of the first cases against sex traffickers and needed a partner for the trial. Coppedge volunteered. Together, they won the case, helping to provide justice for approximately 36 teenage girls. When the other attorney left, Coppedge became the office’s most experienced attorney at handling trafficking cases and continued pressing for justice in the courtroom.

Estimates suggest that 21 million people are victimized by some form of labor or sex trafficking.

“This was an area I felt really called to because of the opportunity to speak on behalf of people who thought no one would ever listen to or believe their stories,” Coppedge said.

Working with the FBI, the Department of Homeland Security, and NGOs, she prosecuted more than 45 human traffickers and assisted approximately 90 victims.

In October 2015, she was appointed by President Obama to serve in her current role. With a staff of about 50 people, Coppedge is responsible for leading the United States’ global engagement against human trafficking.

Ensuring survivors of trafficking have a voice in the criminal justice system is important, she said. She recalls witnessing a victim address her traffickers in court during sentencing. The woman spoke about how she would return to the trafficker’s home each night and cry, worried that only the walls could hear her. The criminal case allowed her to finally tell her story.

“I have told U.S. senators, states’ attorneys general and foreign government leaders her story so everyone can hear her cry,” Coppedge said.

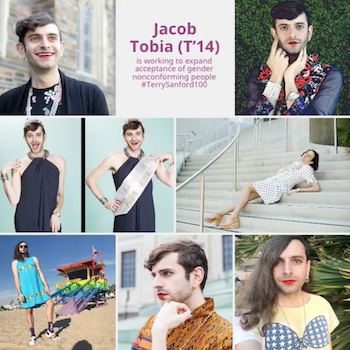

Named as one of Forbes’ 30 Under 30 for 2018, Jacob Tobia (T'14) is working to expand acceptance of gender nonconforming people.

Tobia identifies as genderqueer and non-binary, not male or female. A Benjamin N. Duke scholar, they graduated with a degree in Human Rights Advocacy and spent much of their time as an undergraduate advocating for LGBTQ+ students.

As vice president of equity and outreach on Duke Student Government, co-president of Blue Devils United, and president of Duke Students for Gender Neutrality, Tobia worked to raise awareness and acceptance of marginalized students on campus. They successfully lobbied for gender-neutral housing and restrooms, fought for the expansion of transgender student healthcare, and mobilized students against anti-LGBT policies in North Carolina.

After graduation, Tobia’s passion for furthering LGBTQ+ rights continued as an intern for the Human Rights Campaign. There they created an employee resource group for transgender and genderqueer staff members and helped carry out research on Medicaid policy and HIV/AIDs.

At NBC News, Tobia became writer, producer and host of Queer 2.0, a weekly video series focusing on the LGBTQ+ community. This national platform allowed Tobia to become a recognizable face in the LGBTQ+ movement, rising as a strong voice for nonbinary youth. They have since worked as a social media producer for “Transparent,” an Emmy Award-winning show, and has now sold their memoir “Sissy” to Putnam Books.

“This book feels vital to me because it is about honoring my inner child, about honoring what nonconforming kids go through, about honoring the courage it took to claim my identity in a world that didn’t always make it easy,” Tobia told Entertainment Weekly. “Through writing this book, I’m learning to claim that I deserved better. I deserved to live in a world where, as a feminine kid, I could simply be carefree.”

For Kristina Smith PPS’19, improving the Duke experience for low-income and minority students is at the heart of her work on campus.

As Duke Student Government’s Vice President for Services and Sustainability, Smith works tirelessly to help bolster student resources. Her latest effort, Daily Devil Deals, looks to improve affordability on campus by ensuring every dining vendor provides meal options for $5 or less. The proposal, which Smith brought to the administration, was borne from her realization that while Duke brings together students from varied socioeconomic backgrounds, low-income students may struggle financially on campus. Additionally, Smith believes the initiative helps address aspects of the much criticized freshman meal plan.

Smith’s previous leadership work involved working with the Duke Card Office to get flex increments lowered from $25 to $10 and bringing a local farmer’s market to campus. She is now discussing with financial aid the possibility of opening a “career closet” for students unable to purchase expensive clothes for interviews.

Smith credits her experience as a co-director for Common Ground with influencing her campus advocacy work. The five-day student retreat fosters dialogue about issues of race, socioeconomic status, gender and sexuality.

On her passion for helping students, Smith said, “If I can have a meeting, raise a concern, or lead a conversation that makes someone’s day easier, then it is absolutely worth my time. The work I do is motivated by people’s experiences.”

Lawyer and businessman Michael Sorrell MPP'90/JD’94 took the reins at Paul Quinn College, a historically black college (HBCU) in Dallas on the verge of collapse, in the spring of 2007. The school had mounting debts, crumbling buildings, and falling enrollment. Loss of accreditation seemed likely.

Within a year, Sorrell had gained national attention for extensive fund-raising, instituting a business casual dress code and, in football-crazed Texas, shutting down the football program.

The list of changes and accomplishments during Sorrell’s tenure is impressive. Fifteen abandoned campus buildings were demolished, new admissions standards were established and a Presidential Scholars Program launched. The college completed four consecutive audits without findings, had several years of budget surpluses and received full accreditation from the Transnational Association of Christian Colleges. In 2011 the college was named HBCU of the Year.

An epiphany on a railway platform in India led Sanford alumna Maya Ajmera MPP '93 to her life’s work. Amidst the dust, noise and chaos of the train station, a circle of children sat around a teacher using flash cards to teach them to read. Ajmera learned that it cost about $400 a year to fund the school, which also fed and clothed the children.

Ajmera calls it her “moment of obligation,” when she realized the enormous impact small amounts of money could have at the grassroots level. Instead of going to medical school, Ajmera earned a master’s of public policy degree at the Sanford Institute and used that training to create the nonprofit Global Fund for Children.

With an initial focus on literacy, Ajmera wrote a children’s book as her first project, Children from Australia to Zimbabwe, illustrated with photographs. She wanted to spotlight the beauty and resilience of children in developing countries and show the commonality of children in the “global village.” Money from the book sales funded the program’s first grants, including one to the teacher of that train station school.

Today, GFC continues this twofold approach: making small grants to community-based organizations working with vulnerable children and youth and running a media program of books, documentary film and photography about children. To date, GFC has awarded over $34 million in grants to more than 600 organizations in 78 countries, serving more than 9 million children worldwide.

For Duke biology alumna and medical resident Jennifer Farrell ’04, app development was an unexpected venture, but one that may help to save lives around the world.

While at Duke, Farrell was an on-campus volunteer emergency medical technician. She also participated in the Sanford School’s Hart Leadership Program, which allowed her to pursue her passion for medicine in South Africa. There she implemented a first aid curriculum in 15 schools and experienced her first taste of EMT work overseas.

Following on from this, in 2012 she went to Bangladesh and provided emergency medical response training to around 1,500 people. However, the lack of a 911-style system meant that volunteer first responders had no way of being connected to accidents. In an attempt to bridge this gap, Farrell launched the nonprofit CriticaLink.

The CriticaLink app utilizes location-based mobile networks to alert medical volunteers to nearby accidents. In Bangladesh, where an estimated 82 percent of accident victims die before they reach a hospital, Farrell’s CriticaLink can make the difference between life and death.

Winner of Bangladesh’s National App Award in 2015, CriticaLink has been widely recognized as having significant potential for global application. Based on the success of the pilot phase, which serves the capital city of Dhaka with 150 trained responders, Farrell’s goal is to create a lasting model that operates around the world and provides a life-saving service to those who need it most.

She wrote: “Perhaps I am an idealist, but I was lucky enough to be born in a time and place where I have had incredible opportunities to get an education and be free to pursue my interests, so I wake up every day doing the best I can to try to make the most of these gifts and try to use them to make a positive impact on the world.”

In her years as a Zubrow Fellow at Philadelphia’s Juvenile Law Center, Duke alumna Lauren Fine JD’11 worked on a case that paved the way for her career in child legal services. Shocked by the circumstances facing a 14-year-old boy convicted of homicide, Fine set out to change the way juvenile cases are handled in court.

Her quest for reform led her to launch, in 2014, the Youth Sentencing and Reentry Project (YSRP), a Philadelphia nonprofit that aims for the removal of youth cases from the adult criminal justice system. The organization provides support to lawyers with juvenile clients, advocates for policy reform, and creates child-specific reintegration plans for incarcerated youth and their families.

In 2016, the U.S. Supreme Court decision in Montgomery v. Louisiana guaranteed resentencing for more than 2,000 men and women nationally who were sentenced as children to life in prison without parole. Since then, YSRP is focusing on aiding more than 300 who are from Philadelphia County – the largest concentration of juvenile lifers in the world.

Fine and her partner, Joanna Visser Adjoian, have been recognized for their life-changing work. This includes support from the Black Male Achievement Fellowship, the Echoing Green Fellowship, and the Claneil Emerging Leader Fellowship. Fine also has an impressive list of achievements having been honored as a 2016 American Bar Association Lawyer on the Rise and a 2015 American Express-Ashoka Emerging Innovator.

As co-director of YSRP, Fine hopes to expand outside of Philadelphia in order to give more children a path out of the legal system. Yet, her overall goal is to be rendered unnecessary by eventually ensuring children are not tried as adults.

General Martin Dempsey is a 2016 Rubenstein Fellow at Duke University where he co-taught a course in the Sanford School of Public Policy on American civil-military relations with Duke political scientist Peter Feaver. Dempsey also taught a course on management and leadership at the Fuqua School of Business. For the 18th chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, the experience Dempsey brought to the classroom is the culmination of 41 years of military service in the U.S. Army.

He has earned numerous awards throughout his years of service, including knighthood. Dempsey was named the 18th Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff in 2011, where he served as as the principal military adviser to the president, the secretary of defense and the National Security Council. Prior to becoming chairman, the general served as the Army’s 37th Chief of Staff. His military career included assignments as Commander of the U.S. Army Training and Doctrine Command, Deputy Commander and then Acting Commander of U.S. Central Command, and Commanding General of the Multi-National Security Transition Command in Iraq.

A 1974 graduate of the United States Military Academy, Dempsey earned a master’s degree in English from Duke in 1984, where he developed a friendship with fellow West Point graduate and current Duke men’s basketball coach Mike Krzyzewski. He also holds advanced degrees from the U.S. Army Command and General Staff College and the National War College. In 2014, Dempsey delivered the commencement address at Duke’s graduation ceremony.

Granddaughter of an oil tycoon, Leah Hunt-Hendrix BA’05 perhaps seems like an unlikely figure to be heading up campaigns for progressive social change, but on the contrary, this heiress is using her wealth and platform to do exactly that.

Catalyzed by the Occupy Wall Street movement, Hunt-Hendrix began to reflect on how she could best use her background to aid the struggle for economic and racial equality. From this, Solidaire was born, a foundation that rallies wealthy donors and aligns significant financial resources to help build the infrastructure needed for deep structural changes in society.

In her work as Solidaire’s executive director, Hunt-Hendrix is guided by a deep knowledge of politics and theories of social movements that took root with her Duke degree in political science and grew during her doctoral studies at Princeton in religion, ethics and politics. She seeks to change the face of philanthropy, providing resources directly to exploited communities and calling upon society’s 1% to address the consequences of their own privilege.

Solidaire offers its members several ways to leverage their wealth: pooled giving for collective action or “movement building;” “rapid response” investing in small or urgent needs; or “aligned giving,” a five-year shared commitment. It emphasizes trusting the people on the front lines to take the lead on tactics for creating a solution. Solidaire’s first aligned giving commitment is to support Black-led organizations in the Movement for Black Lives.

On her incentive for Solidaire, she said: “My north star is similar to the one that has guided many of us for centuries. A world where everyone has what they need to flourish. Where no one has far too much or far too little. Where we are not divided by arbitrary prejudice. A world that is made up of beautiful, strong, and loving communities.”

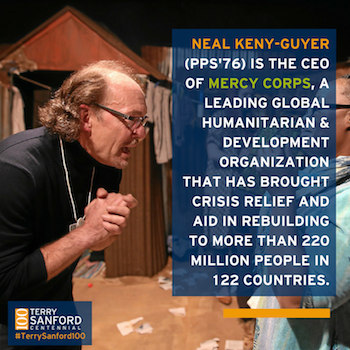

“They inspired me to see my career more as a mission…. I came out very inspired to make a difference,” Neal Keny-Guyer PPS’76, says of his professors in Duke’s public policy program. One of the first graduates of what is now the Sanford School of Public Policy, Keny-Guyer was also one of the earliest social entrepreneurs.

After working with international relief organizations such as UNICEF and Save the Children, Keny-Guyer joined Mercy Corps as chief executive officer in 1994. With his guidance, Mercy Corps has since grown to become a leading global humanitarian and development organization, having brought crisis relief and aid in rebuilding to more than 220 million people in 122 countries.

During Keny-Guyer’s tenure, the organization responded to nearly every global emergency including the Syrian refugee crisis, the Bosnian War, and the South Sudan famine. Currently operating in more than 40 countries and with a staff of 4,500, Mercy Corps is rooted in the belief that strong communities are the best agents for change. Using micro-financing and other tools, Mercy Corps helps local people pursue social and economic change. On a humanitarian trip to the Gaza Strip, Keny-Guyer partnered with Google to create a tech incubator for young entrepreneurs. It gave rise to two of the top 100 businesses in the Middle East.

Among other honors, Mercy Corps earned the Fast Company and Monitor Group 2008 Social Capitalist Award, an accolade given to innovative nonprofits that have “a consistent and unusually large impact on society.” In 2017, the Duke Alumni Association recognized Keny-Guyer for Service to the Global Community.

Accolades aside, it is the drive to maximize human potential that drives Keny-Guyer: “I know change can happen; I’ve witnessed it during my lifetime. I spend 75 percent of my time traveling around the globe to precarious places, where life is incredibly difficult. And yet, I continue to meet the most extraordinary people committing daily acts of heroism despite their circumstances. It is so inspiring and fills me with great hope.”

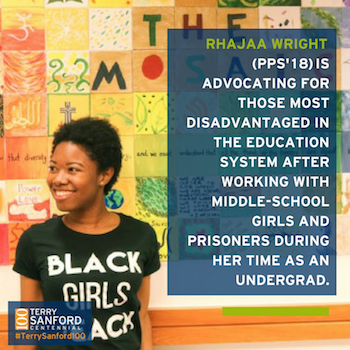

As upperclassmen begin to plan for life after Duke, one senior is confident she has found her calling. After interning with various nonprofits, Rhajaa Wright PPS’18 is pursuing her passion for education by becoming a teacher.

Wright’s first experience working with young people came during the summer after freshman year while volunteering for the Partnership for Appalachian Girls’ Education (PAGE). Mentoring middle-school girls reminded Wright, a first-generation college student, of the value of education. In a bid to incorporate her other passions, music and dance, Wright championed creative education, helped the girls to start a dance class and directed digital storytelling lessons to familiarize them with 21st century technology.

This creative spirit was also shown in her work for the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) in DC, where she spent time corresponding with prisoners. Although working on prison reform was draining, her internship experience opened her eyes to the need for more rehabilitative programs in the justice system, as well as to the disproportionate impact incarceration has on minority populations. With this in mind, Wright is a strong advocate for the power of education as a way to prevent crime and incarceration in vulnerable communities.

Connecting her experiences with PAGE and ACLU, Wright hopes to spend a year working for AmeriCorps in DC public schools under the Empowering Males of Color Initiative (EMOC). Her goal is to advocate for those most disadvantaged in the education system by leading the charge for educational reform. Working with policymakers and urban schools, Wright hopes to implement more innovative teaching methods focusing on the arts, social well-being, and making African American history a bigger part of school curriculums.

On her decision to enter the field of education, Wright said: “As I close out my senior year at Duke, the only job that I can see myself pursuing is one where I can also serve as a mentor, a friend and a revolutionary.”

“Professor Tom Taylor provided guidance throughout his career to leaders across the Pentagon, and now at Duke for the past decade, he has served as a role model for public policy students to take the humble servant's mentality while boldly pursuing better public policies at all levels of government.

In regard to the many ways that he exemplifies Terry Sanford's leadership ethos, it is easy to point to Professor Taylor’s bravery on September 11, 2001, where he saved lives as a first responder at the Pentagon. It is much harder (but even more meaningful) to measure all of the little moments of wit, wisdom, and grace that he has shown his colleagues and students over the course of his career.

Professor Taylor is a genuinely good man who deeply cares for others, and who has made such a lasting impact on me and so many others. Truly, I can think of no better leader than Professor Taylor for the many ways he has inspired, encouraged, and loved those around him -- and I am grateful for the opportunity to nominate him for this recognition, so that the entire Duke community can celebrate him for his humble contributions to student life and public service.”

-- Rob Lalka MPP’08, Executive Director of the Albert Lepage Center for Entrepreneurship and Innovation at Tulane University’s A. B. Freeman School of Business

Remembering Uncle Terry

“I am a 1986 grad and was fortunate that my time overlapped with [Terry Sanford’s]. H. Keith H. Brodie took over for him my Senior Year, but, before that, it was Uncle Terry all the way. I was of course there to receive his Avuncular Letter in 1984.

One of the things that I think was terrific about him was how accessible he was with the student body, and how he loved to engage and interact with us. Everyone was invited to a small group gathering at his house their Freshman Year. He must have held hundreds of those gatherings over the years. When you saw him walking around campus, you could approach and talk to him. He even answered gladly to “Uncle Terry” and he was always upbeat and positive.

In the fall of my junior year, two of us ventured to his office on a Friday afternoon and asked him if we could go to lunch with him. He told us ‘absolutely’ and he asked us to leave our names and phone numbers with his assistant. Several months later, one morning, we received a call asking if we could join Mr. Sanford for lunch. Several of us went. We drove over to the Allen Building in a borrowed Volvo (the nicest car any of our friends had). He insisted he would not ride in a foreign made car and that we switch to his car (I think an Oldsmobile, made in the USA) and he drove us to lunch. The site of us getting into his car as classes were changing was priceless, and many of our friends wondered just what could have been going on when they saw us. He took us to lunch on Main Street in Durham. He signed yearbooks of those who asked. He did not rush things – he acted like there was nothing else in the world he would rather be doing. It took him a while to walk down the street, because a very high percentage of people he passed stopped to say hello to him.

After the 1992 ACC Men’s Basketball Tournament Final in Charlotte, won by Duke (over UNC in the final, 94-74), we saw him with his wife at the bar of the Adams Mark Hotel. He was a Senator at the time. A few of us went over to say hello and he asked us to join him and Mrs. Sanford for a beer.

At graduation in 1986, he was on the stage and he received the loudest cheers and a standing ovation from the student body. Everyone loved him. He did so much good for the world, and that is definitely the most important part of his legacy.”

-Vernon Johnson (T’86)

In the Media

News & Observer: Terry Sanford’s astonishing life and legacy with us still

Charlotte Observer: The importance of Terry Sanford’s legacy today

News & Record: Let's Remember Terry Sanford

News & Record: Sanford appreciated, rewarded initiative

Duke Magazine: Uncle Terry saves the day

Terry Sanford: Legacy of Service

Uncle Terry saves the day

As a former governor, Terry Sanford often used his political skills during his tenure as Duke president, from 1970 to 1985. One of his best-known missives, the “Avuncular Letter,” was sent to the undergraduate students in 1984. At once humorous and chiding, effective but gentle, the letter, signed “Uncle Terry,” is a triumph of Sanford’s acumen. The story behind the letter, however, tells the tale of the long-standing problem facing Sanford, as well as the path it set toward the creation of what we now know as “Cameron Crazies.”

Student rowdiness at basketball games didn’t begin in 1984. In fact, correspondence about the issue in Sanford’s presidential records dates back to 1973. Even then, opposing teams accused enthusiastic Duke fans of spitting on them in Cameron Indoor Stadium. A number of student cheers also contained words some alumni and other viewers felt were unfitting for a school of Duke’s caliber.

After a particularly nasty incident in 1979, in which the wife of the North Carolina State University coach was taunted, Duke fans were reviled in the press. A Richmond Times-Dispatch column by Mike Bevans suggested, “If ABC ever expands its Superstars competition to include collections of raving idiots, put your money on the Duke students who assemble behind press row for every game at Cameron Stadium.”

Sanford wrote a letter to the student body in February 1979, remarking on the volume of letters sent to his office—“more than I have received on any other issue since I have been at Duke.” He warned that the conduct was beginning to interfere with Duke’s reputation, as well as its fundraising. He concluded the letter by saying, “We can have plenty of fun, kid others to whatever degree we want to, but there is a line that decent people simply have to draw. I contend that a Duke student has enough sense to know where to draw the line. I am counting on you to draw it.” The following day, Sanford wrote a letter to all fraternity presidents, asking them to do what they could to keep their members in line.

The presidential caution didn’t curtail all bad behavior, however. At a game in February 1983, Virginia coach Terry Holland found himself with Duke students sitting immediately behind the visitors’ bench, and was on the receiving end of constant insults and enough noise that he had difficulty communicating with his players. “While I admit that I enjoy some of the ideas that Duke students come up with,” Holland wrote dryly to Duke Athletics Director Tom Butters, “the profanity and the personal attacks on coaches and their families really have no place in the college game.”

As the 1983-84 season approached, Sanford wrote, perhaps wearily, to Butters: “With the approaching basketball season, I turn once more to a favorite peeve of mine, and that is the ‘dehumanizing’ conduct of a number of our students at home games. I hope you can devise a plan to minimize this kind of conduct, and to improve the rather sorry reputation our student body has in this respect.” It didn’t take long, however, before the antics in Cameron earned the school renewed attention from the press.

At a game against Maryland in January 1984, a number of students threw underwear and contraceptives onto the court—a dig at a Maryland player who had been accused of sexual misconduct—and sang chants containing four-letter words, hurled personal insults against players and coaches, and created general mayhem. Clippings of critical articles were sent to Sanford, along with letters expressing shock and distaste at the behavior. One read, “To think that some of those same students might within just a few years be our doctors, dentists, lawyers, and legislators boggles one’s mind.” Many asked when the administration was going to step in.

Even his friend Peace Corps founder and politician Sargent Shriver wrote him, expressing sympathy: “What can be done? Short of evicting the ‘fans’ (if they’re worthy of that name) or fining the home team points for foul behavior by home team rooters, I can’t imagine what can or should be done. But I’m guessing you can. So, the purpose of this letter is solely to tell you that a lot of fathers & mothers would rally around a president with the courage to put an end to this kind of despicable conduct.”

It was in response to all of this outcry that Sanford penned his avuncular letter. In it, he implored the fans to be creative, but to keep it clean. “Think of something clever but clean, devastating but decent, mean but wholesome, witty and forceful but G-rated for television, and try it at the next game.” He concluded the letter with a single sentence: “I hate for us to have the reputation of being stupid.” Duke students demonstrated their new and improved behavior at the next home game, against the University of North Carolina. A group of students attempted to deliver a bouquet to UNC coach Dean Smith, and the crowd, many of who were wearing halos, shouted, “Hi Dean!” in greeting. The referees received a standing ovation when they walked onto the court, and when the fans objected to their calls, they shouted, “We beg to differ” rather than their previous favorite cry, which referred to barnyard droppings. Even the signs in the stands were cleaned up: “Welcome honored guests,” and “Sorry Uncle Terry. The devil made us do it.”

The new behavior received positive feedback from almost all, including from UNC. Dean Smith told The Durham Morning Herald, “I’m impressed with the Duke officials and Duke student body that they tried to do something about it.” Slyly, Smith continued, “Of course, I didn’t ever notice the other things.”

The Avuncular Letter didn’t end misbehavior, but it did usher in a new era for Duke men’s basketball fans and began some practices that continue, including line monitors. Within a couple of years, the remarkable fan base was bestowed with the “crazies” moniker. Sanford, with his typical finesse in working with students, alumni, administrators, and colleagues at other schools, helped make the Cameron Crazies into the creative and powerful force they are today.

This article written by Valerie Gillispie was originally published in Duke Magazine.