In Durham, around 46,000 residents have had their driver’s license suspended or revoked. Many of these people lost their driving privileges because they were unable to pay the fines and fees associated with tickets or failed to appear in court.

For minor traffic violations, the consequences can be major and long-lasting (the median suspension length is nearly 12 years). How does losing a license — and getting it back — affect life outcomes for Durham residents? How well is the city’s Durham Expunction & Restoration (DEAR) program helping people get back on the road?

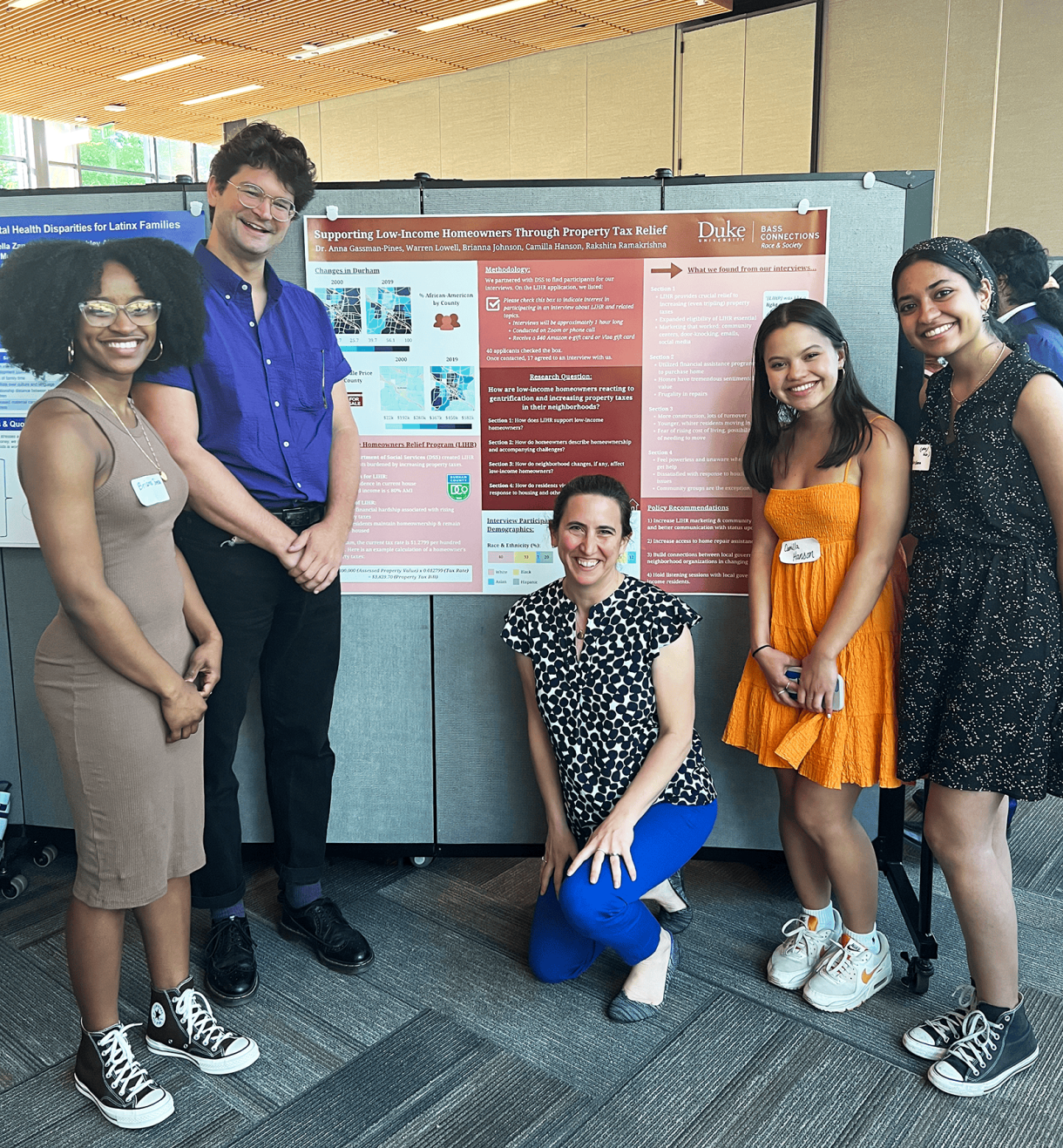

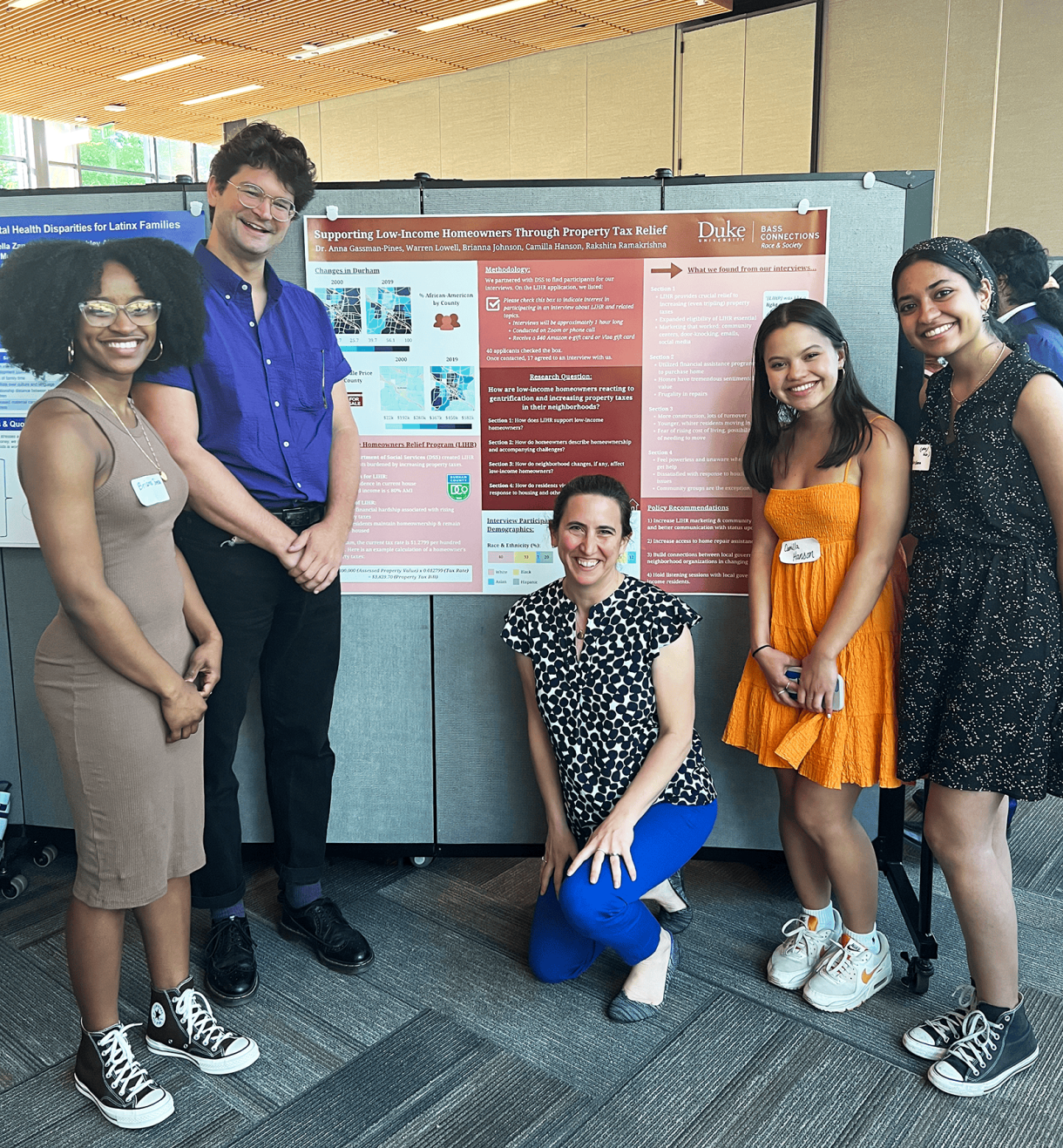

Ph.D. students Adrienne Jones and Warren Lowell spoke with undergraduate student Khilan Walker about their experience co-leading a Bass Connections project, Examining Racial Inequality and Reform Through Driver’s License Access, in collaboration with Professor Anna Gassman-Pines. Here are excerpts from the conversation with Jones and Lowell.

Conversation Excerpts

Why they got involved in this area of research

Adrienne Jones: I am from a really small town in North Carolina, and I have always thought a lot about people’s opportunities for economic mobility based on where they may be located spatially. And I’ve always had a particular interest in Black Americans in the rural South, because that’s my lived experience but also because a lot of researchers aren’t really thinking about this particular group of folks who are near and dear to my heart.

Warren Lowell: I was a social worker before I went back to graduate school. Part of that work took me all over majority-Black neighborhoods in Boston. I started to ask pretty basic questions, like what are the social structures that make schools and homes look so different from neighborhood to neighborhood? I moved to Minneapolis, doing work and interviews with folks in shelters, and it was striking to see the racial disparities in homelessness. It started coming together that this has to be a huge focus of what I’m doing: racial inequality and housing outcomes.

Jones: When Professor Gassman-Pines approached me about the potential to roll onto this project in Durham County around driver’s license suspensions and how they may pose barriers to self-sufficiency, it was really of interest to me.

Lowell: Adrienne is a year above me in the Ph.D. program and had already developed a dissertation plan as I was developing mine. She was leading the project on driver’s license restoration, and we were trying to think of how we could incorporate my interest in housing and gentrification. This coalescing theme became: how do local governments provide financial or other support to folks who need it? I started leading another project, doing interviews with low-income homeowners in Durham to learn more about the property tax relief program that the county is providing.

Centering their community partners

Lowell: We have approached this work from a community-based perspective, meaning that the questions are developed in collaboration with our community partners — Adrienne with DEAR [Durham Expunction & Restoration, which aims to restore suspended licenses by waiving unpaid traffic tickets and fines], and me with the Department of Social Services — to help improve the programs that we’re looking at and provide feedback to them.

Jones: Our DEAR partners have been fantastic to work with. They have been really generous with providing us data and contact information, and sharing about the origins of the program. They want to know how things are going, what are the directions in which they may need to pivot, and they have been really open to hearing about some of the pitfalls that people experience.

Lowell: Professor Gassman-Pines has been helping us think through how we frame the feedback that we give to our community partners.

Jones: We couldn’t do this work if the folks in our community weren’t so kind as to offer us their time and their expertise about their own lived experience. We are trying to be mindful about centering them and their voices in the work that we’re creating, and also thinking critically about ways that we can share back and involve community members, not to be extractive but also, ‘Here is what we learned. How does this resonate with you all? Does this accurately reflect your experiences?’

Leading a team of students

Jones: This project was also an opportunity for me to have some teaching, mentoring and supervision experience working with students at all levels. It’s helping me to think not only about research, but then how do we teach research? How do we translate some of the things that we’ve been thinking about to people who may not have the same level or training or understanding of the project?

Lowell: This was the first year that I led my own team, and I think it requires a lot of nimbleness that I’m fortunate to have developed when I was a social worker … I’ve really enjoyed that because I think it’s activating a part of my brain I haven’t used in a few years.

Jones: This work has become a huge part of my life, and I’m really excited to see where it takes us in the next couple of years.

Adrienne Jones is a joint degree Ph.D. student in Public Policy and Sociology. Broadly, she is interested in the relationship between experiences with employment and inequality.

Warren Lowell is a 4th year Ph.D. candidate in the Sociology and Public Policy joint degree program. He studies the causes and consequences of housing insecurity and inequality in housing markets.

Both have been recognized for their outstanding mentorship of students (Lowell in 2023 and Jones in 2022). Their Bass Connections project team won the program’s 2023 poster competition for “Freedom to Move: Durham Driver’s License Access and the DEAR Program.”