It's no secret that the United States has major issues with gun violence and police brutality, but with a growing distrust between communities facing high rates of gun violence and law enforcement, how can we prevent future crimes and make our communities safer? Judith Kelly, Dean of the Sanford School of Public Policy at Duke University considers this question and more with Professor in the School of Public Policy and author of Policing Gun Violence Philip Cook.

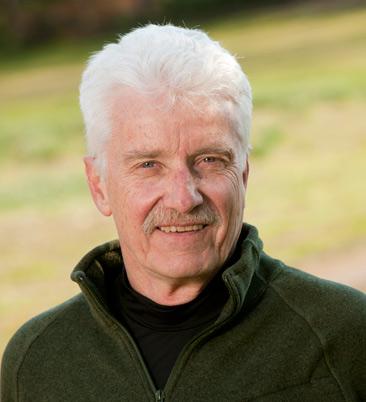

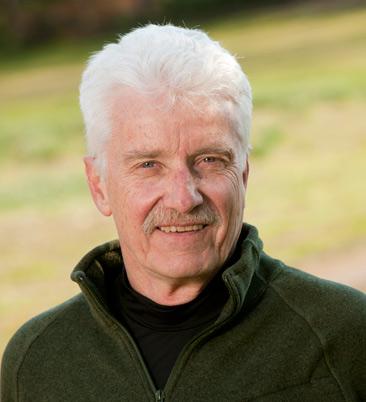

Guest: Philip Cook, emeritus Professor in the Sanford School of Public Policy and author of Policing Gun Violence which came out in February 2023.

- Link to the transcript.

- Read new research related to disparities in police response to fatal and non-fatal shootings in Durham, NC. The report released Feb. 27, 2023 was co-authored by Philip J. Cook and Audrey Vila, a data justice fellow with the Wilson Center for Science and Justice at Duke Law School

- Check out the new book Policing Gun Violence.

Conversation Highlights

Responses have been edited for clarity.

On the connection between COVID-19 and the rise in gun violence

I think that 2020 was the year from hell. First we had the COVID pandemic in the spring and then in May, the murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis. That triggered nationwide protests and international protests against the police and started the defund the police movement. (And the police already were reluctant to engage with the public because of fear of infection from COVID.) [Police] backed off further as a result of the demonstrations and the hostility towards police.

So what we saw is a particular surge in gun violence shortly after the George Floyd murder and [related] demonstrations. And since then, we have been able to document a huge increase in gun sales.

[In addition] we've seen that police not only backed off but [many] have taken early retirement. And it's been very hard to recruit replacements. And so Durham and cities all over the country have a large number of vacancies. The irony is that while the defund [the police] movement was not successful directly, it is true that, in fact, we have a reduced police force these days.

On gun control regulation

I've been working in this area almost 50 years now. And for much of that time, my focus was on regulation and on the ways in which people got their guns and what they did with them. The problem is that the regulations that we've had in place that appear to be most effective are being eroded over time by two processes; one is just the politics of gun control, which has been dominated by the National Rifle Association. And the other is the Supreme Court, which in 2008 discovered that we have a personal right to keep and bear arms in the Second Amendment, and that has put a sharp limit on the kind of regulations that are considered constitutional.

But the most important regulations, in my judgment, have been regulations on carrying guns in public. And in about half the states now, all regulation has been eliminated.

In North Carolina, when I arrived here in 1973, it was illegal to carry a concealed gun. And that was true in a lot of states, even Southern states. But now most anyone can get a permit. It's cheap and easy.

And there's the big push on the part of the legislature to do away with even that regulation and the other kinds of regulations that have mattered, like, I think it's important that we have a permit system and waiting period. But those are again evaporating in the face of political pressure and in the Supreme Court.

What we have left, if we want to control gun violence, is the police. So that was the inspiration for this book. We must have this kind of constructive conversation about the role of the police.

On police brutality

I think currently, for understandable reasons, people have been focused on race and racism, on the part of the police. But the fact is that 75 out of every 100 people shot and killed by the police are not Black. It is disproportionate, but it's still one in four.

And so [one way to look at it is], “Well, the problem is that the police are killing too many people. Period. It’s not that they're just killing too many Black people, but that they're killing too many people.”

It seems to me that it's a more productive conversation in some ways, [is not asking what can be done to] eliminate racism from the police departments, but rather what can be done to find ways to reduce brutality overall and the inclination [by police] be too ready to shoot and use their firearm.

And so the encouraging answer on that starts with the observation that if you look, as we did, at the large cities in this country, we find a very large difference in the rate at which officers kill civilians on a per capita basis.

For example, Phoenix and Dallas, which are two cities that have a lot of similarity in terms of size and composition and crime rates. Phoenix, year in and year out, has five times the rate of officer involved shootings than Dallas does.

And so it is possible then to take a given situation I think and transform it into one with much less brutality and the way to do it is by a commitment on the part of the leadership. A commitment that results in establishing clear rules of engagement, establishing a clear norm that any brutality is not going to be tolerated and a kind of a clear indication of accountability for misbehavior on the part of the officers.

On healing the relationship between communities and the police

It's essential that relationship [between communities and the police] be healed, that it be more positive, that the police are seen as reliable and actually concerned about the well-being of all of the citizens.

In 2020, not only did we have this record-breaking increase in homicide, but we also had a record low in terms of the percentage of the public who had faith in the police. For the Black community, it dropped below 20 percent. So, I would say a good place to start is to have the police start concentrating more on the crimes that the communities care the most about, because what you often hear from communities is that they feel over policed sure enough, but they also feel under policed and neglected by the police. And the evidence that they're neglected is that the shooters are not being arrested.

There's been many years of talk about community policing to improve the relationship directly and if it's possible, to recruit new officers who come from those communities that are most impacted. That's obviously good. And so, if residents personally know the families of the officers, that can be helpful.

About Policy 360

Policy 360 is a series of policy-focused conversations hosted by Judith Kelley, Dean of the Sanford School of Public Policy at Duke University. New episodes premiere bi-weekly. Guests have included luminaries like former Secretary of State Madeleine Albright and former director of the World Bank Jim Yong Kim, as well as researchers from Duke University and other institutions. Conversations are timely and relevant.