Hundreds of people wait in line for the Penn Pavilion event with David Brooks.

David Brooks learned much about himself while writing his latest book, some of which played out publicly.

“I’ve been fortunate enough in my life twice to be interviewed by Oprah. The first was in 2014…, and the second was in 2019. After that second interview, she said, ‘David, I’ve rarely seen someone change so much in middle age. You were so emotionally blocked before.’ She would know! So that was a very proud moment for me. No matter what age you are, a lot of change can happen.”

As Sanford’s latest guest in the Rubenstein Distinguished Lecture series, Brooks walked attendees through that “middle-age change” with humor, humility, and touching anecdotes from his own life and others he has met.

The event was held in a packed Penn Pavilion and was co-sponsored by the Sanford School of Public Policy, the DeWitt Wallace Center, and the Duke Centennial. Brooks, a familiar face on PBS NewsHour and a contributing writer for The New York Times, was introduced by Manoj Mohanan, Interim Dean of Sanford, who praised Brooks for navigating the complexities of human relationships in his recent work, "How to Know a Person: The Art of Seeing Others Deeply and Being Deeply Seen.”

Inspired by his work in this book, Brooks explored the intricacies of human connection in our increasingly dehumanized world. He shared personal anecdotes, research findings, and profound observations, leaving listeners with a renewed appreciation for empathy and genuine connection.

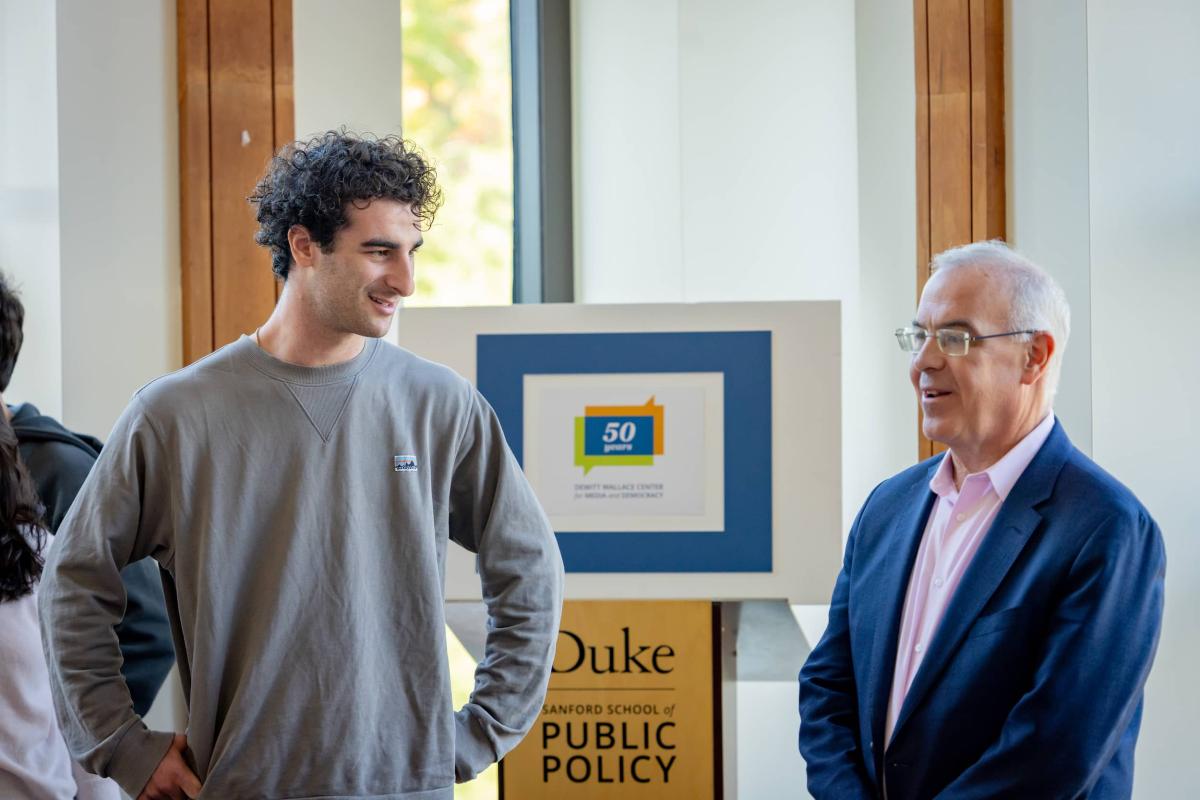

Brooks Meets with Sanford Students

Before his public lecture, Brooks engaged in a more intimate discussion with a select group of Sanford students. Having taught as a visiting fellow with Sanford in 2006-2007, it was a welcome return to a place he loved.

This meeting provided a glimpse into the genesis of his book and his motivations for exploring the topic of human connection. "The personal part of the book is just me trying to be a better human being," Brooks confessed, "but also that my problems are the world's problems."

He shared his belief that the current international crisis of meaning goes beyond economic factors, stating, "It's easy to blame inflation or other societal factors, but it might be something more spiritual and emotional." He also emphasized the importance of individual connection in addressing societal challenges, quoting Emerson's powerful words: "Souls are not saved in bundles. They are saved one by one."

Brooks's Journey Toward Emotional Intelligence

In his public lecture, Brooks candidly admitted his struggles with emotional intelligence. Growing up in a reserved Jewish family, he humorously recalled: "The culture in my home was ‘think Yiddish, act British,’ super-stiff upper lip, never show emotion."

He described his path towards embracing vulnerability and openness, highlighting the role of fatherhood and personal setbacks in his transformation. "Having some failures loosens you up," Brooks confessed.

A Society in Need of Connection

Brooks painted a stark picture of American society grappling with loneliness, distrust, and despair. "The number of Americans who say that no one knows me well is 54%," he revealed, emphasizing the urgent need for connection. He attributed this crisis, in part, to a societal failure to teach essential social skills: "For a couple of generations now, we have neglected to teach people the social skills needed to be centered to people and the complex circumstances of life."

Diminishers vs. Illuminators

Brooks introduced the concepts of "diminishers" and "illuminators" to illustrate the impact individuals have on others. "Diminishers are people who are un-curious about you," he explained. "The other kind of people are called illuminators and those are people are curious about it, they make you feel lit up." He stressed the importance of cultivating the qualities of an illuminator to foster meaningful connections.

The Art of Conversation

Brooks emphasized conversation as a cornerstone of human connection. He offered practical tips for enhancing conversational skills, such as being a "loud listener," embracing pauses ("Don't fear the pause"), and asking thought-provoking questions. He encouraged the audience to adopt a storytelling approach to questions, prompting others to share their experiences and values. "I've learned in the course of my journalism career to ask storytelling questions," Brooks shared. "So I don't ask people, 'What do you believe?' I ask, 'How'd you come to believe that?'"

Navigating Difficult Conversations

Brooks acknowledged the challenges of navigating difficult conversations, particularly those involving sensitive topics or differing viewpoints. He shared personal experiences, including a confrontation with an angry stranger. "When somebody comes at you with a difference and with critique," Brooks advised, "your first job is to stand in their standpoint…Tell me more about your point of view. What am I missing here?" He underscored the importance of empathy, respect, and a willingness to understand different perspectives.

The Power of Seeing and Being Seen

Brooks shared stories about the profound impact of feeling seen and understood. He relayed an experience from one of his students in which she was comforted by a group of friends. After being overwhelmed by the memory of her father’s death, she was embraced by a group of friends without a single word exchanged.

He also reflected on a moment of deep connection with his wife, during which he felt he truly saw her essence. "It was almost as if I wasn't seeing her; I was seeing out from her," he described. He emphasized that the ability to see and be seen is a fundamental human need.

A Call to Humanism

Brooks concluded with a powerful message of humanism: He described humanism as “being human in defiance of social conditions around." He urged the audience to embrace their shared humanity and connect with others in defiance of society's dehumanizing forces. He emphasized that everyone has the potential for both darkness and light, and he encouraged the audience to see themselves in others, fostering empathy and understanding.

"It is still worth it to go through your life as a trusting person. Most of the time, you'll bring out the best in others."

David Brooks

A Conversation with Lisa Borders

Following his lecture, Brooks engaged in a lively and insightful conversation with Lisa Borders, a Duke alumna (T'79) and current member of the university's Board of Trustees. Borders, a recognized leader with experience in the private, public, and non-profit sectors, has held positions such as President of the WNBA and Vice Mayor of Atlanta. She brought her unique perspective to the discussion, delving deeper into the nuances of empathy with Brooks.

He defined empathy as a skill that can be cultivated and honed, outlining its three key components: mirroring, mentalizing, and caring. "People think empathy is you just gush forward your heart," Brooks explained, "but it's a lot more than that." He also discussed the concept of emotional granularity, emphasizing the importance of being attuned to one's own emotions and those of others. "The most important thing you do is done in your body, not in your brain," he reiterated.

Advice for Students and Faculty

Brooks offered specific advice for students: "Pick 5 or 10 of your best Duke friends and form a giving circle…so you can walk through life with people who knew you when." He also encouraged them to "widen their horizon of risk" by embracing new experiences and challenges after graduation.

He highlighted the importance of openness in the classroom for faculty: "If you can show some vulnerability, it just will change your relationship in the classroom."

Choosing trust in others instead of skepticism

In a culminating moment in his talk, Brooks spoke of our world marked by anger and division and implored the audience to resist the urge to withdraw and instead embrace vulnerability and trust. "It is still worth it to go through your life as a trusting person," he asserted. "Most of the time, you'll bring out the best in others."

"I've learned in the course of my journalism career to ask storytelling questions. So I don't ask people, 'What do you believe?' I ask, 'How'd you come to believe that?'"

David Brooks

Student Perspective

Students Reflect on David Brooks' Visit

Duke undergraduates Lily Kempczinski and Lauren Pehlivanian (both writers for the 9th Street Journal) and first-year MPP student Michael Schmitz reflect on Brooks' visit.